Our dollar, your problem

You can subscribe to receive these notes by email here

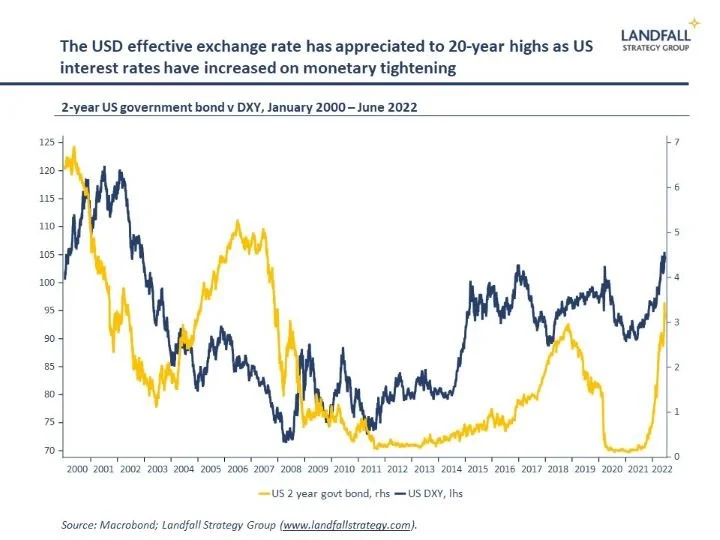

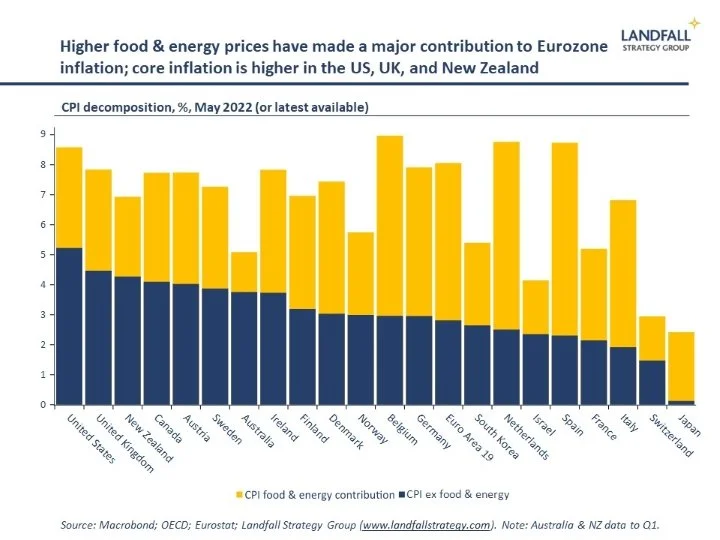

The US Federal Reserve increased policy rates by 75bp last week. Market pricing is for the policy rate to increase to over 3% by the end of the year, up from 0.25% in January. Borrowing rates in the US have increased to reflect this. This is a response to surging inflation in the US, which is due more to excess demand than higher energy prices (see ‘chart of the week’ at the bottom of the note).

Rapidly tightening monetary conditions will have an impact on the US economy. A recession is seen as increasingly likely; and US equity markets have moved into bear market territory over the past few weeks.

The central role of the US in the global financial and economic system means that these monetary policy decisions will also have substantial effects across the global economy. And structurally, these dynamics will intersect with a fragmenting global economic system.

Economic spillovers

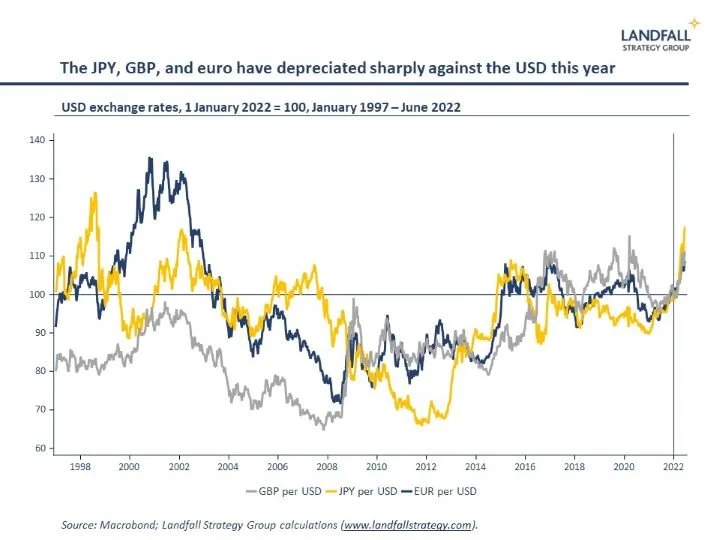

Relatively tight US monetary policy is having significant effects on exchange rates around the world. The US trade weighted exchange rate is at 20-year highs; the yen is at a 24-year low against the USD, down >30% since January 2021; and the euro and GBP have also slumped.

Exchange rate moves of this magnitude can create costs and pressures as competitive positions are altered. US listed firms have taken substantial write-downs because of weaker foreign investment income in USD terms. And even when the exchange rate depreciates, volatility can still create challenges – including a higher cost of imported goods. Some of these shocks can be long-lasting, enduring after the exchange rate movement unwinds.

And economies with USD pegs (e.g. Hong Kong, Gulf states) import US monetary policy; monetary policy has to tighten in order to maintain the peg even when domestic economic conditions do not call for it. In Hong Kong, for example, monetary conditions are tightening to maintain the USD peg despite weak GDP growth (partly because of Covid lockdowns).

A stronger USD also creates challenges for world trade growth. Because the vast majority of world trade is denominated in USD, a stronger USD increases the cost of imported goods and services – and so reduces demand. A strong USD also changes the cost and availability of trade finance. Periods of USD strength tend to be associated with weaker growth in world merchandise trade volumes.

World merchandise trade growth has been resilient through the pandemic, recovering strongly from the lows in 2020 (so fast that global supply chain disruptions were created). But combined with slowing world GDP growth, strong USD appreciation is likely to weaken the pace of world trade growth. These exchange rate effects can be costly for small economies that have large export shares, and that are deeply exposed to the strength of world trade.

Monetary tightening in the US also creates exposures among developing countries; a higher USD often leads to capital outflows and higher borrowing costs. The World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects downgraded the outlook for developing countries, noting that ‘financial crises have been more likely when U.S. monetary policy pivots toward a more aggressive tightening stance’.

We can expect monetary tightness to cause additional stresses across many indebted emerging markets – at the same time as higher food and energy prices. This economic stress is likely to lead to social and political turbulence as well.

Global fragmentation

The global economy is fragmenting, as geopolitical competition and domestic political pressures increasingly shape trade and investment flows. It seems likely that some of the economic pressures from tight US monetary policy will interact with these fragmentation dynamics.

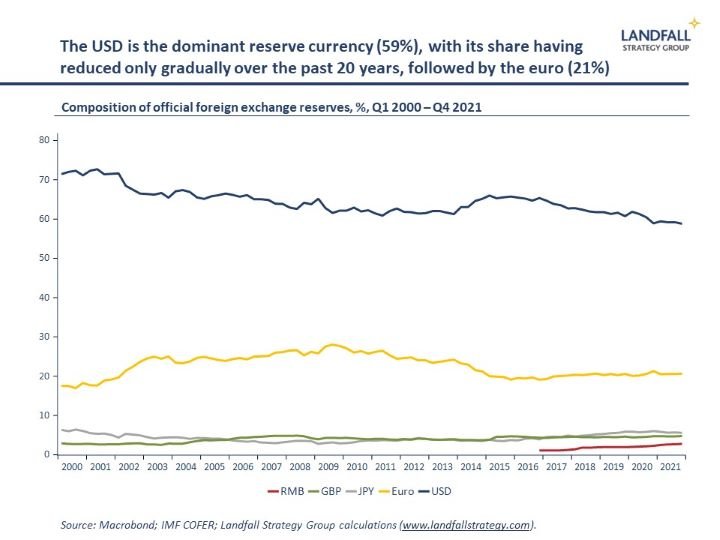

The dominance of the USD has been a central part of globalisation over the past several decades. And the USD remains dominant as a reserve currency on every available metric: ~60% of official reserves; and it is involved in ~90% of international transactions. The Fed is also the world’s central bank, with swap lines to many other central banks.

This dominance is unlikely to change materially anytime soon. There is some reserve diversification underway on the margin, into currencies like the AUD, CAD, and SEK. A strongly valued USD is a good time to diversify reserves. But there are no clear at-scale alternatives to the USD; and an international consensus on a new global system is difficult in the current global environment, when all economic instruments are being weaponised.

‘You cannot replace something with nothing… (what are the alternatives to the USD) when Europe’s a museum, Japan’s a nursing home, China’s a jail, and Bitcoin’s an experiment?’, Larry Summers

But exchange rate regimes are geopolitical statements as well as economic calculations, and it would be surprising if the global financial system was not impacted by fragmentation dynamics (see this from the IMF’s Chief Economist). For example, there is debate in China about the merits of holding >USD1 trillion of USD assets in its official reserves (with another USD500 billion in Hong Kong) given the changing geopolitical environment – and having seen the Western freezing of Russia’s central bank reserves. Although the USD is in no near-term danger of being dethroned, China and others are looking to reduce exposure to the USD.

And tight monetary conditions will interact with geopolitical dynamics to raise questions about the sustainability of some USD pegs. For example, the HKD remains pegged against USD even as China walks away from the ‘one country, two systems’ approach. The HKD peg has worked well as a credible anchor, even as the US has become a less important economic partner over the past few decades. But it does not seem politically sustainable as Hong Kong moves into the second half of the 50 year handover period.

Other USD pegs, such as those in the Gulf states are also up for question as their trading relations move towards Asia. As with trading relations, it seems likely that there will be increasing alignment between currency arrangements and political values over time: friends will share currency arrangements as well as trade and investment flows.

What happens in DC doesn’t stay in DC

‘The dollar is our currency, but it's your problem’, US Treasury Secretary John Connally (1971)

The US sets monetary policy for its own context, as it did when it unilaterally exited the gold standard in 1971, but this has spillovers into the global economy. The current rate hiking cycle will cause disruptions around the world in the near-term, and will reinforce structural changes in the global financial system.

US monetary policy will remain central to the global economy, but some countries (notably China) are looking to reduce USD exposures over time – and to align exchange rate strategy with geopolitical positioning: gradually diversifying reserves, reviewing exchange rate arrangements, changing the denomination currency for some international transactions (e.g. for commodities), and developing digital currencies.

As the global economy fragments, so too will global currency arrangements. Currency fragmentation will likely move at a slower pace than trade fragmentation, but governments and firms should expect changes to global currency and financial arrangements that have prevailed for the past several decades. The stresses associated with tight US monetary policy may reinforce this process.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

Chart of the week

Higher energy and food prices, importantly due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have contributed to the surge in inflation around the world. However, there is substantial variation. In the US and UK, inflation is due to domestic conditions to a greater extent than in the Eurozone, where higher energy and food prices are the dominant driver of higher inflation (~65% of the contribution to CPI inflation v ~40% in the US). This means that US monetary policy is likely to remain tighter than in the Eurozone.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

www.twitter.com/dskilling