When the tides goes out

After resilient growth through the pandemic, world trade flows are slowing – reflecting a slowing global economy. And as the G20 meetings in Bali last week demonstrated – as well as other recent corporate and political developments – firms and governments are continuing to position for a reshaped global economic and political system.

But the ebbing global economic tide may make some of these structural shifts more challenging to navigate.

Global slowdown

Global trade flows are beginning to weaken. Monthly growth in the CPB world trade series has been decelerating through 2022, although it remains positive (to August). More recent estimates from the Kiel Institute also show slowing, but still positive, growth.

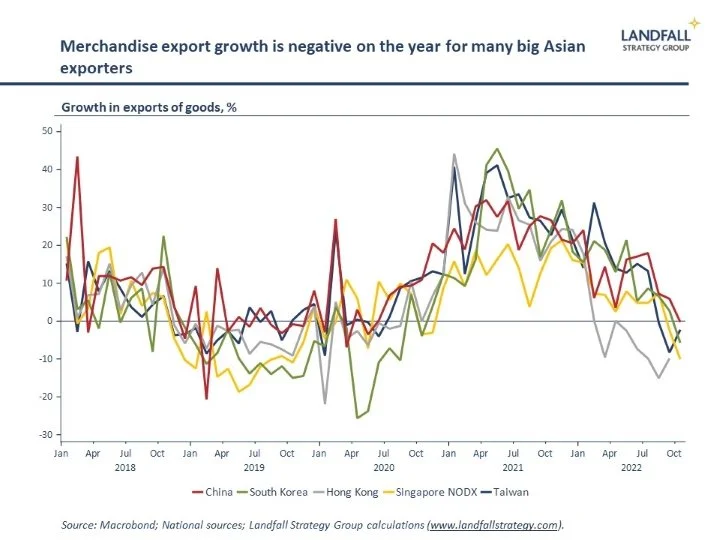

However, recent data for many Asian exporting economies, manufacturing powerhouses that provide a useful bellwether for the strength of world trade, paint a weaker picture. South Korean exports are contracting, as are exports from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. And China’s imports and exports came in below expectations in October.

Across the broader small advanced economy group, export growth has turned. And the WTO is picking markedly lower trade growth (1%) next year.

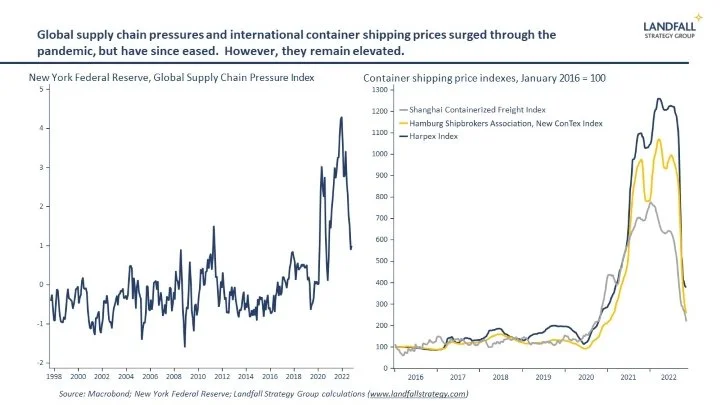

This changed demand profile is reflected in global supply chains. Significant supply chain disruptions were seen through the pandemic. Strong growth in demand for durable goods contributed to massive increases in international shipping prices and delays. But these pressures have unwound significantly, with prices, congestion, and delays down sharply.

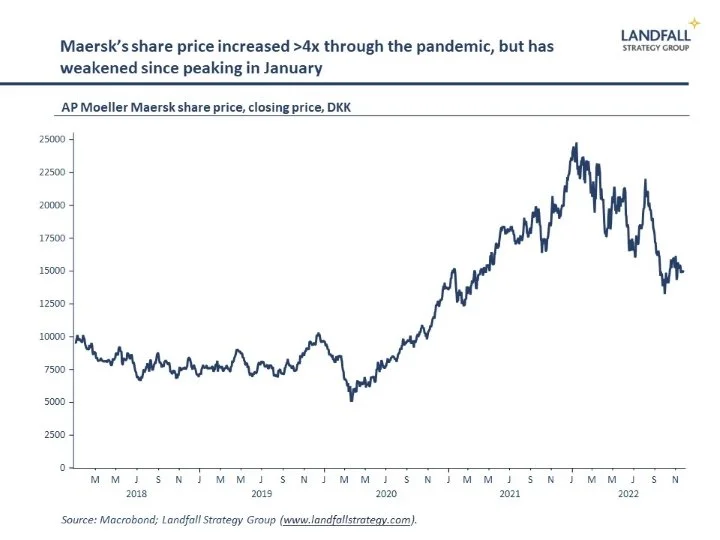

This is partly a reflection of post-Covid disruptions easing, but importantly also reducing demand as the global economy slows. Indeed, AP Moeller Maersk – the Danish shipping company – which had recorded record profits through the pandemic is forecasting a weaker outlook on contracting global container demand. Its share price is a useful barometer of the expected strength of globalisation.

On the plus side, there will be some support from a weakening USD. After a period of substantial USD appreciation (on higher rates, safe haven flows, and positive external balance dynamics), the looming end of the Fed rate hiking cycle is taking pressure off the USD. A weaker USD is generally associated with stronger world trade growth.

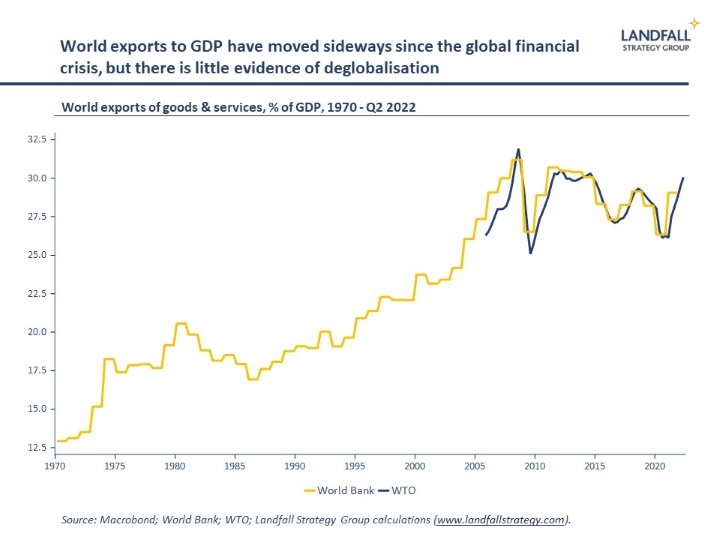

These slowing global trade flows are not evidence of deglobalisation: world exports as a share of GDP are holding up well. And the decline in forecast trade growth largely reflects weakening GDP growth. The OECD’s latest Economic Outlook, released this week, forecast weaker GDP growth across the OECD (0.8%) and the world (2.2%) in 2023.

Competing, but more quietly

But the underlying shape of global flows is shifting – driven by changing economics, geopolitical rivalry, and domestic politics.

The single most important relationship in the world is that between the US and China. The G20 meetings in Bali last week lowered the temperature of this relationship, with the first face to face meeting between Presidents Biden and Xi (both fresh off the back of political successes at home).

Although these US/China conversations did not alter the fundamental trajectory of the relationship, it re-opened channels of communication and served to develop some guardrails. This is valuable given the very high level of economic interdependence between the US and China: a hard, unmanaged rupture in relations would impose substantial costs.

Indeed, a recent report by the Rhodium Group (reportedly prepared for the State Department), estimated that a Chinese blockade of Taiwan would generate annual direct costs of $2.5 trillion (~2.6% of current world GDP). Substantial additional indirect costs would be likely. This would be catastrophic for the global economy.

US/China trade relations are at close to record levels despite the geopolitical tensions. But the strategic rivalry between the US and China will continue to play out on economic, financial, and technology domains, as well as on military grounds. The sweeping semiconductor restrictions imposed by the US on China are one example.

And this week Apple announced that it would be sourcing its chips from a TSMC facility in Arizona (currently being built), supported by US industrial policy support. This is part of an ongoing diversification strategy for Apple: India and Vietnam are also becoming more important production platforms. Reshoring and measure of decoupling is underway, even if gradual and sector-specific.

But as discussed in my previous note, the emerging global context is more complicated than a simple bipolar world. Also at the G20 meetings, the Australian PM met with President Xi with a view to stabilising relations. Australia wants China to lift sanctions on a wide range of Australian exports. Italy announced plans to expand economic relations with China. And the German Chancellor was in Beijing earlier this month with a business delegation.

Many Western economies are actively balancing economic and political objectives, trying to carve out strategic space where possible. For example, the Dutch Government is under pressure from the US to limit ASML’s engagement with China – but have warned that they will not simply copy US measures. Indeed, agreements were signed between the Netherlands and South Korea last week on semiconductors, another country that is wary of direct US/China technology competition.

And there are emerging poles in the global economy that are trying to preserve flexibility. For example, Qatar has just signed the longest ever LNG supply deal (27 years) with China’s Sinopec. And there are deepening links between many Gulf states and China, with some change in the strategic posture of countries like Saudi Arabia. More generally, a range of middle powers – from Indonesia to India – are looking to position themselves in a multipolar world.

Globalisation in a zero sum world

Appropriately as Thanksgiving weekend is being celebrated, there are some positives in all of this. The G20 and APEC meetings made progress on managing some of the political risks to the global economy, managing to issue closing statements with a measure of consensus. [And encouragingly, the G20 meeting was able to agree on wording to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; Russia is increasingly ostracised.]

This is welcome, but should not be over-interpreted. The logic of strategic geopolitical competition remains intact, even if economic tail risks have been managed. Politics is back, and big powers are moving away from the support of an open, rules-based system to a more discretionary system in which they can directly advance their interests.

Aggressive industrial policy is just one example of these big power tendencies, which will lead to a more fragmented global economic system. The US, China, and the EU (to a lesser extent) are competing for control of the commanding heights of the C21 global economy.

Other economies are looking to balance geopolitical pressures (and the need to make choices), with the imperative to capture value from economic and trade relations. Performing in this world will be much more demanding than in the relatively depoliticised global economy of the past few decades. This is particularly the case for small advanced economies, deeply exposed to globalisation and geopolitical rivalry. Small economies – and firms – will need to win market share by strengthening competitive advantage, and successfully navigating geopolitical cross-currents.

‘It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who has been swimming naked’, Warren Buffett

These structural shifts in the global economy have accelerated over the past few years. But the post-Covid surge in world trade may have covered over some of the structural shifts underway in the global system. Weaker/negative growth in global trade flows will add zero sum dynamics to global competition. An ebbing global economic tide adds complexity and risk to what is already a challenging world.

If you are not subscribed yet and would like to receive these small world notes directly by email, you can subscribe here:

We provide insights and advisory services to firms, investors, and governments on responding to global economic and geopolitical dynamics. Please do get in touch with me at contact@landfallstrategy.com if you would like to discuss how we can support you.

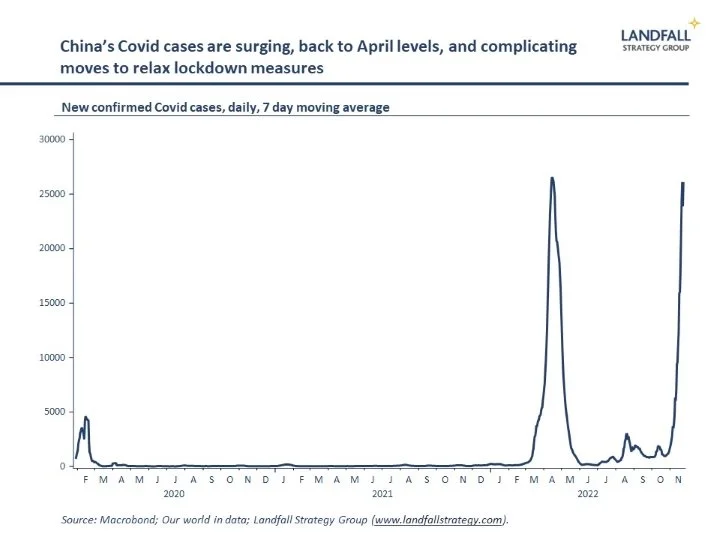

Chart of the week

Reported Covid cases in China have been moving up sharply over the past few weeks; the 7 day moving average is now over 25,000 new cases a day. China has been pursuing rolling lockdowns in pursuit of zero Covid. And although President Xi and others have been signalling some relaxation of measures, the increase in cases complicates the trajectory. The speed with which China opens up domestically is an important factor for the global economic outlook and markets.

Dr David Skilling

Director, Landfall Strategy Group

www.landfallstrategy.com

https://davidskilling.substack.com